Friday, November 29, 2019

STORY OF TROY

Head of Homer.

British Museum.

ECLECTIC SCHOOL READINGS

THE STORY OF TROY

BY

M. CLARKE

NEW YORK—CINCINNATI—CHICAGO

AMERICAN BOOK COMPANY

COPYRIGHT, 1897, BY

AMERICAN BOOK COMPANY

CONTENTS.

| PAGE | ||

| INTRODUCTION— | Homer, the Father of Poetry | 7 |

| The Gods and Goddesses | 11 | |

| I. | Troy before the Siege | 19 |

| II. | The Judgment of Paris | 33 |

| III. | The League against Troy | 46 |

| IV. | Beginning of the War | 63 |

| V. | The Wrath of Achilles | 76 |

| VI. | The Dream of Agamemnon | 92 |

| VII. | The Combat between Menelaus and Paris | 109 |

| VIII. | The First Great Battle | 124 |

| IX. | The Second Battle—Exploit of Diomede and Ulysses | 149 |

| X. | The Battle at the Ships—Death of Patroclus | 166 |

| XI. | End of the Wrath of Achilles—Death of Hector | 193 |

| XII. | Death of Achilles—Fall and Destruction of Troy | 220 |

| XIII. | The Greek Chiefs after the War | 240 |

INTRODUCTION.

I. HOMER, THE FATHER OF POETRY.

In this book we are to tell the story of Troy, and particularly of the famous siege which ended in the total destruction of that renowned city. It is a story of brave warriors and heroes of 3000 years ago, about whose exploits the greatest poets and historians of ancient times have written. Some of the wonderful events of the memorable siege are related in a celebrated poem called the Ilʹi-ad, written in the Greek language. The author of this poem was Hoʹmer, who was the author of another great poem, the Odʹys-sey, which tells of the voyages and adventures of the Greek hero, U-lysʹses, after the taking of Troy.

Homer has been called the Father of Poetry, because he was the first and greatest of poets. He lived so long ago that very little is known about him. We do not even know for a certainty when or where he was born. It is believed, however, that he lived in the ninth century before Christ, and[Pg 8] that his native place was Smyrʹna, in Asia Minor. But long after his death several other cities claimed the honor of being his birthplace.

Seven Grecian cities vied for Homer dead,Through which the living Homer begged his bread.

Leonidas.

It is perhaps not true that Homer was so poor as to be obliged to beg for his bread; but it is probable that he earned his living by traveling from city to city through many parts of Greece and Asia Minor, reciting his poems in the palaces of princes, and at public assemblies. This was one of the customs of ancient times, when the art of writing was either not known, or very little practiced. The poets, or bards, of those days committed their compositions to memory, and repeated them aloud at gatherings of the people, particularly at festivals and athletic games, of which the ancient Greeks were very fond. At those games prizes and rewards were given to the bards as well as to the athletes.

It is said that in the latter part of his life the great poet became blind, and that this was why he received the name of Homer, which signified a blind person. The name first given to him, we are told, was Mel-e-sigʹe-nes, from the river Meʹles, a small stream on the banks of which his native city of Smyrna was situated.[Pg 9]

So little being known of Homer's life, there has been much difference of opinion about him among learned men. Many have believed that Homer never existed. Others have thought that the Iliad and Odyssey were composed not by one author, but by several. "Some," says the English poet, Walter Savage Landor, "tell us that there were twenty Homers, some deny that there was ever one." Those who believe that there were "twenty Homers" think that different parts of the two great poems—the Iliad and Odyssey—were composed by different persons, and that all the parts were afterwards put together in the form in which they now appear. The opinion of most scholars at present, however, is that Homer did really exist, that he was a wandering bard, or minstrel, who sang or recited verses or ballads composed by himself, about the great deeds of heroes and warriors, and that those ballads, collected and arranged in after years in two separate books, form the poems known as the Iliad and Odyssey.

Homer's poetry is what is called epic poetry, that is, it tells about heroes and heroic actions. The Iliad and Odyssey are the first and greatest of epic poems. In all ages since Homer's time, scholars have agreed in declaring them to be the finest poetic productions of human genius. No nation in[Pg 10] the world has ever produced poems so beautiful or so perfect. They have been read and admired by learned men for more than 2000 years. They have been translated into the languages of all civilized countries. In this book we make many quotations from the fine translation of the Iliad by our American poet, William Cullen Bryant. We quote also from the well-known translation by the English poet, Alexander Pope.

The ancients had a very great admiration for the poetry of Homer. We are told that every educated Greek could repeat from memory any passage in the Iliad or Odyssey. Alexander the Great was so fond of Homer's poems that he always had them under his pillow while he slept. He kept the Iliad in a richly ornamented casket, saying that "the most perfect work of human genius ought to be preserved in a box the most valuable and precious in the world."

So great was the veneration the Greeks had for Homer, that they erected temples and altars to him, and worshiped him as a god. They held festivals in his honor, and made medals bearing the figure of the poet sitting on a throne and holding in his hands the Iliad and Odyssey. One of the kings of Eʹgypt built in that country a magnificent temple, in which was set up a statue of Homer, surrounded[Pg 11] with a beautiful representation of the seven cities that contended for the honor of being the place of his birth.

Great bard of Greece, whose ever-during verseAll ages venerate, all tongues rehearse;Could blind idolatry be justly paidTo aught of mental power by man display'd,To thee, thou sire of soul-exalting song,That boundless worship might to thee belong.

Hayley.

II. THE GODS AND GODDESSES.

To understand the Story of Troy it is necessary to know something about the gods and goddesses, who played so important a part in the events we are to relate. We shall see that in the Troʹjan War nearly everything was ordered or directed by a god or goddess. The gods, indeed, had much to do in the causing of the war, and they took sides in the great struggle, some of them helping the Greeks and some helping the Trojans.

The ancient Greeks believed that there were a great many gods. According to their religion all parts of the universe,—the heavens and the earth, the sun and the moon, the ocean, seas, and rivers, the mountains and forests, the winds and storms,—were ruled by different gods. The gods, too, it[Pg 12] was supposed, controlled all the affairs of human life. There were a god of war and a god of peace, and gods of music, and poetry, and dancing, and hunting, and of all the other arts or occupations in which men engaged.

The gods, it was believed, were in some respects like human beings. In form they usually appeared as men and women. They were passionate and vindictive, and often quarreled among themselves. They married and had children, and needed food and drink and sleep. Sometimes they married human beings, and the sons of such marriages were the heroes of antiquity, men of giant strength who performed daring and wonderful feats. The food of the gods was Am-broʹsia, which conferred immortality and perpetual youth on those who partook of it; their drink was a delicious wine called Necʹtar.

The gods, then, were immortal beings. They never died; they never grew old, and they possessed immense power. They could change themselves, or human beings, into any form, and they could make themselves visible or invisible at pleasure. They could travel through the skies, or over earth or ocean, with the rapidity of lightning, often riding in gorgeous golden chariots drawn by horses of immortal breed. They were greatly feared by men, and when any disaster occurred,—if lives were lost[Pg 13] by earthquake, or shipwreck, or any other calamity,—it was attributed to the anger of some god.

Though immortal beings, however, the gods were subject to some of the physical infirmities of humanity. They could not die, but they might be wounded and suffer bodily pain the same as men. They often took part in the quarrels and wars of people on earth, and they had weapons and armor like human warriors.

The usual place of residence of the principal gods was on the top of Mount O-lymʹpus in Greece. Here they dwelt in golden palaces, and they had a Council Chamber where they frequently feasted together at grand banquets, celestial music being rendered by A-polʹlo, the god of minstrelsy, and the Muses, who were the divinities of poetry and song.

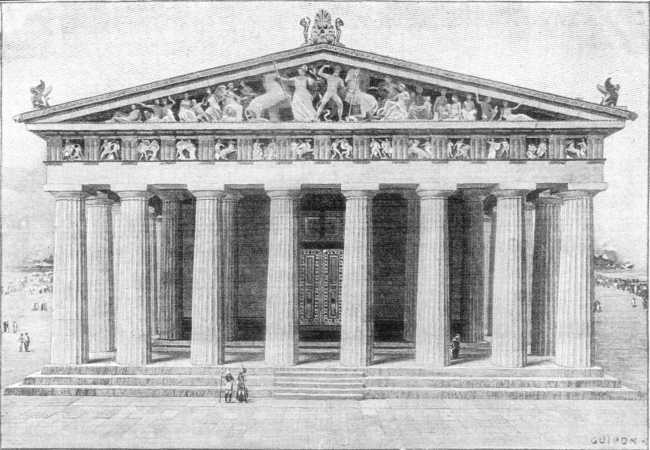

In all the chief cities grand temples were erected for the worship of the gods. One of the most famous was the Parʹthe-non, at Athens. At the shrines of the gods costly gifts in gold and silver were presented, and on their altars, often built in the open air, beasts were killed and burned as sacrifices, which were thought to be very pleasing to the divine beings to whom they were offered.

The Parthenon.

From model in Metropolitan Museum, New York.

The greatest and most powerful of the gods was Juʹpi-ter, also called Jove or Zeus. To him all the rest were subject. He was the king of the gods,[Pg 15] the mighty Thunderer, at whose nod Olympus shook, and at whose word the heavens trembled. From his great power in the regions of the sky he was sometimes called the "cloud-compelling Jove."

He, whose all-conscious eyes the world behold,The eternal Thunderer sat, enthroned in gold.High heaven the footstool of his feet he makes,And wide beneath him all Olympus shakes.

Pope, Iliad, Book VIII.

The wife of Jupiter, and the queen of heaven, was Juʹno, who, as we shall see, was the great enemy of Troy and the Trojans. One of the daughters of Jupiter, called Veʹnus, or Aph-ro-diʹte, was the goddess of beauty and love. Nepʹtune was the god of the sea. He usually carried in his hand a trident, or three-pronged scepter, the emblem of his authority.

His sumptuous palace-halls were builtDeep down in ocean, golden, glittering, proofAgainst decay of time.

Bryant, Iliad, Book XIII.

Mars was the god of war, and Pluʹto, also called Dis and Haʹdes, was god of the regions of the dead. One of the most glorious and powerful of the gods was Apollo, or Phœʹbus, or Sminʹtheus, for he had many names. He was god of the sun, and of medicine, music, and poetry. He is repre[Pg 16]sented as holding in his hand a bow, and sometimes a lyre. Homer calls him the "god of the silver bow," and the "far-darting Apollo," for the ancients believed that with the dart of his arrow he sent down plagues upon men whenever they offended him.

The other principal deities mentioned by Homer are Mi-nerʹva, or Palʹlas, the goddess of wisdom; Vulʹcan, the god of fire; and Merʹcu-ry, or Herʹmes, the messenger of Jupiter. Vulcan was also the patron, or god, of smiths. He had several forges; one was on Mount Olympus, and another was supposed to be under Mount Ætʹna in Sicʹi-ly. Here, with his giant workmen, the Cyʹclops, he made thunderbolts for Jupiter, and sometimes armor and weapons of war for earthly heroes.

The gods, it was believed, made their will known to men in various ways,—sometimes by the flight of birds, frequently by dreams, and sometimes by appearing on earth under different forms, and speaking directly to kings and warriors. Very often men learned the will of the gods by consulting seers and soothsayers, or augurs,—persons who were supposed to have the power of foretelling events. There were temples also where the gods gave answers through priests. Such answers were called Orʹa-cles, and this name was also given to the priests. The most celebrated oracle of ancient[Pg 17] times was in the temple of Apollo at Delʹphi, in Greece. To this place people came from all parts of the world to consult the god, whose answers were given by a priestess called Pythʹi-a.

The ancients never engaged in war or any other important undertaking without sacrificing to the gods or consulting their oracles or soothsayers. Before going to battle they made sacrifices to the gods. If they were defeated in battle they regarded it as a sign of the anger of Jupiter, or Juno, or Minerva, or Apollo, or some of the other great beings who dwelt on Olympus. When making leagues or treaties of peace, they called the gods as witnesses, and prayed to Father Jupiter to send terrible punishments on any who should take false oaths, or break their promises. In the story of the Trojan War we shall find many examples of such appeals to the gods by the chiefs on both sides.

"O Father Jove, who rulest from the topOf Ida, mightiest one and most august!Whichever of these twain has done the wrong,Grant that he pass to Pluto's dwelling, slain,While friendship and a faithful league are ours.

"O Jupiter most mighty and august!Whoever first shall break these solemn oaths,So may their brains flow down upon the earth,—Theirs and their children's."

Bryant, Iliad, Book III.

Offering to Minerva.

Painting by Gaudemaris.

THE STORY OF TROY.

I. TROY BEFORE THE SIEGE.

Design by Burne-Jones.

That part of Asia Minor which borders the narrow channel now known as the Dar-da-nellesʹ, was in ancient times called Troʹas. Its capital was the city of Troy, which stood about three miles from the shore of the Æ-geʹan Sea, at the foot of Mount Ida, near the junction of two rivers, the Simʹo-is, and the Sca-manʹder or Xanʹthus. The people of Troy and Troas were called Trojans.

Some of the first settlers in northwestern Asia Minor, before it was called Troas,[Pg 20] came from Thrace, a country lying to the north of Greece. The king of these Thraʹcian colonists was Teuʹcer. During his reign a prince named Darʹdanus arrived in the new settlement. He was a son of Jupiter, and he came from Samʹo-thrace, one of the many islands of the Ægean Sea. It is said that he escaped from a great flood which swept over his native island, and that he was carried on a raft of wood to the coast of the kingdom of Teucer. Soon afterwards he married Teucer's daughter. He then built a city for himself amongst the hills of Mount Ida, and called it Dar-daʹni-a; and on the death of Teucer he became king of the whole country, to which he gave the same name, Dardania.

Jove was the father, cloud-compelling Jove,Of Dardanus, by whom Dardania firstWas peopled, ere our sacred Troy was builtOn the great plain,—a populous town; for menDwelt still upon the roots of Ida freshWith Qiany springs.

Bryant, Iliad, Book XX.

Dardanus was the ancestor of the Trojan line of kings. He had a grandson named Tros, and from him the city Troy, as well as the country Troas, took its name. The successor of King Tros was his son Iʹlus. By him Troy was built, and it was therefore also called Ilʹi-um or Ilʹi-on; hence the[Pg 21] title of Homer's great poem,—the Iliad. From the names Dardanus and Teucer the city of Troy has also been sometimes called Dardania and Teuʹcri-a, and the Trojans are often referred to as Dardanians and Teucrians. Ilus was succeeded by his son La-omʹe-don, and Laomedon's son Priʹam was king of Troy during the famous siege.

The story of the founding of Troy is a very interesting one. Ilus went forth from his father's city of Dardania, in search of adventures, as was the custom of young princes and heroes in those days; and he traveled on until he arrived at the court of the king of Phrygʹi-a, a country lying east of Troas. Here he found the people engaged in athletic games, at which the king gave valuable prizes for competition. Ilus took part in a wrestling match, and he won fifty young men and fifty maidens,—a strange sort of prize we may well think, but not at all strange or unusual in ancient times, when there were many slaves everywhere. During his stay in Phrygia the young Dardanian prince was hospitably entertained at the royal palace. When he was about to depart, the king gave him a spotted heifer, telling him to follow the animal, and to build a city for himself at the place where she should first lie down to rest.

Ilus did as he was directed. With his fifty[Pg 22] youths and fifty maidens he set out to follow the heifer, leaving her free to go along at her pleasure. She marched on for many miles, and at last lay down at the foot of Mount Ida on a beautiful plain watered by two rivers, and here Ilus encamped for the night. Before going to sleep he prayed to Jupiter to send him a sign that that was the site meant for his city. In the morning he found standing in front of his tent a wooden statue of the goddess Minerva, also called Pallas. The figure was three cubits high. In its right hand it held a spear, and in the left, a distaff and spindle.

This was the Pal-laʹdi-um of Troy, which afterwards became very famous. The Trojans believed that it had been sent down from heaven, and that the safety of their city depended upon its preservation. Hence it was guarded with the greatest care in a temple specially built for the purpose.

Ilus, being satisfied that the statue was the sign for which he had prayed, immediately set about building his city, and thus Troy was founded. It soon became the capital of Troas and the richest and most powerful city in that part of the world. During the reign of Laomedon, son of Ilus, its mighty walls were erected, which in the next reign withstood for ten years all the assaults of the Greeks. These walls were the work of no human[Pg 23] hands. They were built by the ocean god Neptune. This god had conspired against Jupiter and attempted to dethrone him, and, as a punishment, his kingdom of the sea was taken away from him for one year, and he was ordered to spend that time in the service of the king of Troy.

In building the great walls, Neptune was assisted by Apollo, who had also been driven from Olympus for an offense against Jupiter. Apollo had a son named Æs-cu-laʹpi-us, who was so skilled a physician that he could, and did, raise people from death to life. Jupiter was very angry at this. He feared that men might forget him and worship Æsculapius. He therefore hurled a thunderbolt at the great physician and killed him. Enraged at the death of his son, Apollo threatened to destroy the Cyclops, the giant workmen of Vulcan, who had forged the terrible thunderbolt. Before he could carry out his threat, however, Jupiter expelled him from heaven. He remained on earth for several years, after which he was permitted to return to his place among the gods on the top of Mount Olympus.

Neptune.

National Museum, Athens.

Though Neptune was bound to serve Laomedon for one year, there was an agreement between them that the god should get a certain reward for building the walls. But when the work was finished the Trojan king refused to keep his part of the bar[Pg 25]gain. Apollo had assisted by his powers of music. He played such tunes that he charmed even the huge blocks of stone, so that they moved themselves into their proper places, after Neptune had wrenched them from the mountain sides and had hewn them into shape. Moreover, Apollo had taken care of Laomedon's numerous flocks on Mount Ida. During the siege, Neptune, in a conversation with Apollo before the walls of Troy, spoke of their labors in the service of the Trojan king:

"Hast thou forgot, how, at the monarch's prayer,We shared the lengthen'd labors of a year?Troy walls I raised (for such were Jove's commands),And yon proud bulwarks grew beneath my hands:Thy task it was to feed the bellowing drovesAlong fair Ida's vales and pendant groves."

Pope, Iliad, Book XXI.

Long before this, however, the two gods had punished Laomedon very severely for breaking his promise. Apollo, after being restored to heaven, sent a plague upon the city of Troy, and Neptune sent up from the sea an enormous serpent which killed many of the people.

A great serpent from the deep,Lifting his horrible head above their homes,Devoured the children.

Lewis Morris.

[Pg 26]In this terrible calamity the king asked an oracle in what way the anger of the two gods might be appeased. The answer of the oracle was that a Trojan maiden must each year be given to the monster to be devoured. Every year, therefore, a young girl, chosen by lot, was taken down to the seashore and chained to a rock to become the prey of the serpent. And every year the monster came and swallowed up a Trojan maiden, and then went away and troubled the city no more until the following year, when he returned for another victim. At last the lot fell on He-siʹo-ne, the daughter of the king. Deep was Laomedon's grief at the thought of the awful fate to which his child was thus doomed.

But help came at an unexpected moment. While, amid the lamentations of her family and friends, preparations were being made to chain Hesione to the rock, the great hero, Herʹcu-les, happened to visit Troy. He was on his way home to Greece, after performing in a distant eastern country one of those great exploits which made him famous in ancient story. The hero undertook to destroy the serpent, and thus save the princess, on condition that he should receive as a reward certain wonderful horses which Laomedon just then had in his possession. These horses were given to Laome[Pg 27]don's grandfather, Tros, on a very interesting occasion. Tros had a son named Ganʹy-mede, a youth of wonderful beauty, and Jupiter admired Ganymede so much that he had him carried up to heaven to be cupbearer to the gods—to serve the divine nectar at the banquets on Mount Olympus.

Godlike Ganymede, most beautifulOf men; the gods beheld and caught him upTo heaven, so beautiful was he, to pourThe wine to Jove, and ever dwell with them.

Bryant, Iliad, Book XX.

To compensate Tros for the loss of his son, Jupiter gave him four magnificent horses of immortal breed and marvelous fleetness. These were the horses which Hercules asked as his reward for destroying the serpent. As there was no other way of saving the life of his daughter, Laomedon consented. Hercules then went down to the seashore, bearing in his hand the huge club which he usually carried, and wearing his lion-skin over his shoulders. This was the skin of a fierce lion he had strangled to death in a forest in Greece, and he always wore it when going to perform any of his heroic feats.

When Hesione had been bound to the rock, the hero stood beside her and awaited the coming of the serpent. In a short time its hideous form emerged from beneath the waves, and darting for[Pg 28]ward it was about to seize the princess, when Hercules rushed upon it, and with mighty strokes of his club beat the monster to death. Thus was the king's daughter saved and all Troy delivered from a terrible scourge. But when the hero claimed the reward that had been agreed upon, and which he had so well earned, Laomedon again proved himself to be a man who was neither honest nor grateful. Disregarding his promise, and forgetful, too, of what he and his people had already suffered as a result of his breach of faith with the two gods, he refused to give Hercules the horses.

The hero at once went away from Troy, but not without resolving to return at a convenient time and punish Laomedon. This he did, not long afterwards, when he had completed the celebrated "twelve labors" at which he had been set by a Grecian king, whom Jupiter commanded him to serve for a period of years because of an offense he had committed. One of these labors was the killing of the lion. Another was the destroying of the Lerʹnæ-an hydra, a frightful serpent with many heads, which for a long time had been devouring man and beast in the district of Lerʹna in Greece.

Having accomplished his twelve great labors and ended his term of service, Hercules collected an army and a fleet, and sailed to the shores of Troas.[Pg 29] He then marched against the city, took it by surprise, and slew Laomedon and all his sons, with the exception of Po-darʹces, afterwards called Priam. This prince had tried to persuade his father to fulfill the engagement with Hercules, for which reason his life was spared. He was made a slave, however, as was done in ancient times with prisoners taken in war. But Hesione ransomed her brother, giving her gold-embroidered veil as the price of his freedom. From this time he was called Priam, a word which in the Greek language means "purchased." Hesione also prevailed upon Hercules to restore Priam to his right as heir to his father's throne, and so he became king of Troy. Hesione herself was carried off to Greece, where she was given in marriage to Telʹa-mon, king of Salʹa-mis, a friend of Hercules.

Priam reigned over his kingdom of Troas many years in peace and prosperity. His wife and queen, the virtuous Hecʹu-ba, was a daughter of a Thracian king. They had nineteen children, many of whom became famous during the great siege. Their eldest son, Hecʹtor, was the bravest of the Trojan heroes. Their son Parʹis it was, as we shall see, who brought upon his country the disastrous war. Another son, Helʹe-nus, and his sister Cas-sanʹdra, were celebrated soothsayers.[Pg 30]

Cassandra was a maiden of remarkable beauty. The god Apollo loved her so much that he offered to grant her any request if she would accept him as her husband. Cassandra consented and asked for the power of foretelling events, but when she received it, she slighted the god and refused to perform her promise. Apollo was enraged at her conduct, yet he could not take back the gift he had bestowed. He decreed, however, that no one should believe or pay any attention to her predictions, true though they should be. And so when Cassandra foretold the evils that were to come upon Troy, even her own people would not credit her words. They spoke of her as the "mad prophetess."

Cassandra cried, and cursed the unhappy hour;Foretold our fate; but by the god's decree,All heard, and none believed the prophecy.

Vergil.

The first sorrow in the lives of King Priam and his good queen came a short time before the birth of Paris, when Hecuba dreamed that her next child would bring ruin upon his family and native city. This caused the deepest distress to Priam and Hecuba, especially when the soothsayer Æsʹa-cus declared that the dream would certainly be fulfilled. Then, though they were tender and loving parents, they made up their minds to sacrifice their own feel[Pg 31]ings rather than that such a calamity should befall their country. When the child was born, the king, therefore, ordered it to be given to Ar-che-laʹus, one of the shepherds of Mount Ida, with instructions to expose it in a place where it might be destroyed by wild beasts. The shepherd, though very unwilling to do so cruel a thing, was obliged to obey, but on returning to the spot a few days afterwards he found the infant boy alive and unhurt. Some say that the child had been nursed and carefully tended by a she-bear. Archelaus was so touched with pity at the sight of the innocent babe smiling in his face, that he took the boy to his cottage, and, giving him the name Paris, brought him up as one of his own family.

With the herdsmen on Mount Ida, Paris spent his early years, not knowing that he was King Priam's son. He was a brave youth, and of exceeding beauty.

"His sunny hairCluster'd about his temples like a god's."

Tennyson, Œnone.

He was skilled, too, in all athletic exercises, he was a bold huntsman, and so brave in defending the shepherds against the attacks of robbers that they called him Alexander, a name which means a protector of men. Thus the young prince became[Pg 32] a favorite with the people who lived on the hills. Very happy he was amongst them, and amongst the flocks which his good friend and foster father, Archelaus, gave him to be his own. He was still more happy in the company of the charming nymph Œ-noʹne, the daughter of a river god; and he loved her and made her his wife. But this happiness was destined not to be of long duration. The Fates[A] had decreed it otherwise. Œnone the beautiful, whose sorrows have been the theme of many poets, was to lose the love of the young shepherd prince, and the dream of Hecuba was to have its fulfillment.

The FateThat rules the will of Jove had spun the daysOf Paris and Œnone.

Quintus Smyrnæus.

[A]The Fates were the three sisters, Cloʹtho, Lachʹe-sis, and Atʹro-pos, powerful goddesses who controlled the birth and life of mankind, Clotho, the youngest, presided over the moment of birth, and held a distaff in her hand; Lachesis spun out the thread of human existence (all the events and action's of man's life); and Atropos, with a pair of shears which she always carried, cut this thread at the moment of death.

II. THE JUDGMENT OF PARIS.

It was through a quarrel among the three goddesses, Juno, Venus, and Minerva, that Œnone, the fair nymph of Mount Ida, met her sad fate, and that the destruction of Troy was brought about. The strife arose on the occasion of the marriage of Peʹleus and Theʹtis. Peleus was a king of Thesʹsa-ly, in Greece, and one of the great heroes of those days. Thetis was a daughter of the sea god Neʹre-us, who had fifty daughters, all beautiful sea nymphs, called "Ne-reʹi-des," from the name of their father. Their duty was to attend upon the greater sea gods, and especially to obey the orders of Neptune.

Thetis was so beautiful that Jupiter himself wished to marry her, but the Fates told him she was destined to have a son who would be greater than his father. The king of heaven having no desire that a son of his should be greater than himself, gave up the idea of wedding the fair nymph of the sea, and consented that she should be the wife of Peleus, who had long loved and wooed her. But Thetis, being a goddess, was unwilling to marry a mortal man. However, she[Pg 34] at last consented, and all the gods and goddesses, with one exception, were present at the marriage feast.

For in the elder time, when truth and worthWere still revered and cherished here on earth,The tenants of the skies would oft descendTo heroes' spotless homes, as friend to friend;There meet them face to face, and freely shareIn all that stirred the hearts of mortals there.

Catullus (Martin's tr.).

The one exception was Eʹris, or Dis-corʹdi-a, the goddess of discord. This evil-minded deity had at one time been a resident of Olympus, but she caused so much dissension and quarreling there that Jupiter banished her forever from the heavenly mansions. The presence of such a being as a guest on so happy an occasion was not very desirable, and therefore no invitation was sent to her.

Thus slighted, the goddess of discord resolved to have revenge by doing all that she could to disturb the peace and harmony of the marriage feast. With this evil purpose she suddenly appeared in the midst of the company, and threw on the table a beautiful golden apple, on which were inscribed the words, "Let it be given to the fairest."

"This was cast upon the board,When all the full-faced presence of the godsRanged in the halls of Peleus; whereuponRose feud, with question unto whom 'twere due."

Tennyson, Œnone.

[Pg 35]At once all the goddesses began to claim the glittering prize of beauty. Each contended that she was the "fairest," and therefore should have the

"fruit of pure Hesperian goldThat smelt ambrosially."

But soon the only competitors were Juno, Venus, and Minerva, the other goddesses having withdrawn their claims. The contest then became more bitter, and at last Jupiter was called upon to act as judge in the dispute. This delicate task the king of heaven declined to undertake. He knew that whatever way he might decide, he would be sure to offend two of the three goddesses, and thereby destroy the peace of his own household. It was necessary, however, that an umpire should be chosen to put an end to the strife, and doubtless it was the decree of the Fates that the lot should fall on the handsome young shepherd of Mount Ida. His wisdom and prudence were well known to the gods, and all seemed to agree that he was a fit person to decide so great a contest.

Paris was therefore appointed umpire. By Jupiter's command the golden apple was sent to him, to be given to that one of the three goddesses whom he should judge to be the most beautiful. The goddesses themselves were directed to appear before[Pg 36] him on Mount Ida, so that, beholding their charms, he might be able to give a just decision. The English poet, Tennyson, in his poem "Œnone," gives a fine description of the three contending deities standing in the presence of the Trojan prince, each in her turn trying, by promise of great reward, to persuade him to declare in her favor. Juno spoke first, and she offered to bestow kingly power and immense wealth upon Paris, if he would award the prize to her.

"She to Paris madeProffer of royal power, ample ruleUnquestion'd. . . . . . . .'Honor,' she said, 'and homage, tax and toll,From many an inland town and haven large.'"

Minerva next addressed the judge, and she promised him great wisdom and knowledge, as well as success in war, if he would give the apple to her.

Then Venus approached the young prince, who all the while held the golden prize in his hand. She had but few words to say, for she was confident in the power of her beauty and the tempting bribe she was about to offer.

"She with a subtle smile in her mild eyes,The herald of her triumph, drawing nighHalf-whisper'd in his ear, 'I promise thee[Pg 37]The fairest and most loving wife in Greece.'She spoke and laugh'd."

The subtle smile and the whispered promise won the heart of Paris. Forgetful of Œnone, and disregarding the promises of the other goddesses, he awarded the prize to Venus.

He consign'dTo her soft hand the fruit of burnished rind;And foam-born Venus grasp'd the graceful meed,Of war, of evil war, the quickening seed.

Coluthus (Elton's tr.).

Such was the famous judgment of Paris. It was perhaps a just decision, for it may be supposed that Venus, being the goddess of beauty, was really the most beautiful of the three. But the story does not give us a very high idea of the character of Paris, who now no longer took pleasure in the company of Œnone. All his thoughts and affections were turned away from her by the promise of Venus. He had grown weary, too, of his simple and innocent life among his flocks and herds on the mountain. He therefore wished much for some adventure that would take him away from scenes which had become distasteful to him.

Paris.

Vatican, Rome.

The opportunity soon came. A member of King Priam's family having died, it was announced that[Pg 39] the funeral would be celebrated by athletic games, as was the custom in ancient times. Paris resolved to go down to the city and take part in these games. Prizes were to be offered for competition, and one of the prizes was to be the finest bull that could be picked from the herds on Mount Ida. Now it happened that the bull selected belonged to Paris himself, but it could not be taken without his consent. He was willing, however, to give it for the games on condition that he should be permitted to enter the list of competitors.

The condition was agreed to, and so the shepherd prince parted from Œnone and went to the funeral games at Troy. He intended, perhaps, to return sometime, but it was many years before he saw the fair nymph of Mount Ida again,—not until he was about to die of a wound received from one of the Greeks in the Trojan War. Œnone knew what was to happen, for Apollo had conferred upon her the gift of prophecy, and she warned Paris that if he should go away from her he would bring ruin on himself and his country, telling him also that he would seek for her help when it would be too late to save him. These predictions, as we shall see, were fulfilled. Œnone's grief and despair in her loneliness after the departure of Paris are touchingly described in Tennyson's poem:[Pg 40]

"O happy Heaven, how canst thou see my face?O happy earth, how canst thou bear my weight?O death, death, death, thou ever-floating cloud,There are enough unhappy on this earth,Pass by the happy souls, that love to live:I pray thee, pass before my light of life,And shadow all my soul, that I may die.Thou weighest heavy on the heart within,Weigh heavy on my eyelids: let me die."

At the athletic games in Troy everybody admired the noble appearance of Paris, but nobody knew who he was. In the competitions he won all the first prizes, for Venus had given him godlike strength and swiftness. He defeated even Hector, who was the greatest athlete of Troy. Hector, angry at finding himself and all the highborn young men of the city beaten by an unknown stranger, resolved to put him to death, and Paris would probably have been killed, had he not fled for safety into the temple of Jupiter. Cassandra, who happened to be in the temple at the time, noticed Paris closely, and observing that he bore a strong resemblance to her brothers, she asked him about his birth and age. From his answers she was satisfied that he was her brother, and she at once introduced him to the king. Further inquiries were then made. The old shepherd, Archelaus, to whom Paris had been delivered in his infancy to be ex[Pg 41]posed on Mount Ida, was still living, and he came and told his story. Then King Priam and Queen Hecuba joyfully embraced and welcomed their son, never thinking of the terrible dream or of the prophecy of Æsacus. Hector, no longer angry or jealous, was glad to see his brother, and proud of his victories in the games. Everybody rejoiced except Cassandra. She knew the evil which was to come to Troy through Paris, but nobody would give credit to what the "mad prophetess" said.

Thus restored to his high position as a prince of the royal house of Troy, Paris now resided in his father's palace, apparently contented and happy. But the promise made to him on Mount Ida, which he carefully concealed from his family, was always in his mind. His thoughts were ever turned toward Greece, where dwelt the fairest woman of those times. This was Helen, wife of Men-e-laʹus, king of Sparʹta, celebrated throughout the ancient world for her matchless beauty. Paris had been promised the fairest woman for his wife, and he felt sure that it could be no other than the far-famed Helen. To Greece therefore he resolved to go, as soon as there should be an excuse for undertaking what was then a long and dangerous voyage of many weeks, though in our day it is no more than a few hours' sail.[Pg 42]

The occasion was found when King Priam resolved to send ambassadors to the island of Salamis to demand the restoration of his sister

///////////////////////////////////////////////////

RULDIARY REF https://www.gutenberg.org/files/16990/16990-h/16990-h.htm

Thursday, November 28, 2019

PAX BRITTANICA

THE OUTLINE OF

HISTORY

Being a Plain History of Life and Mankind

BY

H. G. WELLS

WRITTEN WITH THE ADVICE AND EDITORIAL HELP OF

MR. ERNEST BARKER,

SIR H. H. JOHNSTON, SIR E. RAY LANKESTER

AND PROFESSOR GILBERT MURRAY

AND ILLUSTRATED BY

J. F. HORRABIN

VOLUME I

New York

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

1920

All rights reserved

Copyright, 1920,

By THE MACMILLAN COMPANY.

By H. G. WELLS.

Set up and electrotyped. Published November, 1920.

NORWOOD PRESS

J. S. Cushing Co.—Berwick & Smith Co.

Norwood, Mass., U.S.A.

BY

H. G. WELLS

WRITTEN WITH THE ADVICE AND EDITORIAL HELP OF

MR. ERNEST BARKER,

SIR H. H. JOHNSTON, SIR E. RAY LANKESTER

AND PROFESSOR GILBERT MURRAY

AND ILLUSTRATED BY

J. F. HORRABIN

VOLUME I

New York

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

1920

All rights reserved

Copyright, 1920,

By THE MACMILLAN COMPANY.

By H. G. WELLS.

Set up and electrotyped. Published November, 1920.

NORWOOD PRESS

J. S. Cushing Co.—Berwick & Smith Co.

Norwood, Mass., U.S.A.

INTRODUCTION

“A philosophy of the history of the human race, worthy of its name, must begin with the heavens and descend to the earth, must be charged with the conviction that all existence is one—a single conception sustained from beginning to end upon one identical law.”—Friedrich Ratzel.

THIS Outline of History is an attempt to tell, truly and clearly, in one continuous narrative, the whole story of life and mankind so far as it is known to-day. It is written plainly for the general reader, but its aim goes beyond its use as merely interesting reading matter. There is a feeling abroad that the teaching of history considered as a part of general education is in an unsatisfactory condition, and particularly that the ordinary treatment of this “subject” by the class and teacher and examiner is too partial and narrow. But the desire to extend the general range of historical ideas is confronted by the argument that the available time for instruction is already consumed by that partial and narrow treatment, and that therefore, however desirable this extension of range may be, it is in practice impossible. If an Englishman, for example, has found the history of England quite enough for his powers of assimilation, then it seems hopeless to expect his sons and daughters to master universal history, if that is to consist of the history of England, plus the history of France, plus the history of Germany, plus the history of Russia, and so on. To which the only possible answer is that universal history is at once something more and something less than the aggregate of the national histories to which we are accustomed, that it must be approached in a different spirit and dealt with in a different manner. This book seeks to justify that answer. It has been written primarily to show that history as one whole is amenable to a more broad and comprehensive handling than is the history of special nations and periods, a broader handling that will bring it within the normal limitations of time and energy set to the reading and education of an ordinary citizen. This outline deals with ages and races and nations, where the ordinary history deals with reigns and pedigrees and campaigns; but it will not be found to be more crowded with names and dates, nor more difficult to follow and understand. History is no exception amongst the sciences; as the gaps fill in, the outline simplifies; as the outlook broadens, the clustering multitude of details dissolves into general laws. And many topics of quite primary interest to mankind, the first appearance and the growth of scientific knowledge for example, and its effects upon human life, the elaboration of the ideas of money and credit, or the story of the origins and spread and influence of Christianity, which must be treated fragmentarily or by elaborate digressions in any partial history, arise and flow completely and naturally in one general record of the world in which we live.

The need for a common knowledge of the general facts of human history throughout the world has become very evident during the tragic happenings of the last few years. Swifter means of communication have brought all men closer to one another for good or for evil. War becomes a universal disaster, blind and monstrously destructive; it bombs the baby in its cradle and sinks the food-ships that cater for the non-combatant and the neutral. There can be no peace now, we realize, but a common peace in all the world; no prosperity but a general prosperity. But there can be no common peace and prosperity without common historical ideas. Without such ideas to hold them together in harmonious co-operation, with nothing but narrow, selfish, and conflicting nationalist traditions, races and peoples are bound to drift towards conflict and destruction. This truth, which was apparent to that great philosopher Kant a century or more ago—it is the gist of his tract upon universal peace—is now plain to the man in the street. Our internal policies and our economic and social ideas are profoundly vitiated at present by wrong and fantastic ideas of the origin and historical relationship of social classes. A sense of history as the common adventure of all mankind is as necessary for peace within as it is for peace between the nations.

Such are the views of history that this Outline seeks to realize. It is an attempt to tell how our present state of affairs, this distressed and multifarious human life about us, arose in the course of vast ages and out of the inanimate clash of matter, and to estimate the quality and amount and range of the hopes with which it now faces its destiny. It is one experimental contribution to a great and urgently necessary educational reformation, which must ultimately restore universal history, revised, corrected, and brought up to date, to its proper place and use as the backbone of a general education. We say “restore,” because all the great cultures of the world hitherto, Judaism and Christianity in the Bible, Islam in the Koran, have used some sort of cosmogony and world history as a basis. It may indeed be argued that without such a basis any really binding culture of men is inconceivable. Without it we are a chaos.

Remarkably few sketches of universal history by one single author have been written. One book that has influenced the writer very strongly is Winwood Reade’s Martyrdom of Man. This dates, as people say, nowadays, and it has a fine gloom of its own, but it is still an extraordinarily inspiring presentation of human history as one consistent process. Mr. F. S. Marvin’s Living Past is also an admirable summary of human progress. There is a good General History of the World in one volume by Mr. Oscar Browning. America has recently produced two well-illustrated and up-to-date class books, Breasted’s Ancient Times and Robinson’s Medieval and Modern Times, which together give a very good idea of the story of mankind since the beginning of human societies. There are, moreover, quite a number of nominally Universal Histories in existence, but they are really not histories at all, they are encyclopædias of history; they lack the unity of presentation attainable only when the whole subject has been passed through one single mind. These universal histories are compilations, assemblies of separate national or regional histories by different hands, the parts being necessarily unequal in merit and authority and disproportionate one to another. Several such universal histories in thirty or forty volumes or so, adorned with allegorical title pages and illustrated by folding maps and plans of Noah’s Ark, Solomon’s Temple, and the Tower of Babel, were produced for the libraries of gentlemen in the eighteenth century. Helmolt’s World History, in eight massive volumes, is a modern compilation of the same sort, very useful for reference and richly illustrated, but far better in its parts than as a whole. Another such collection is the Historians’ History of the World in 25 volumes. The Encyclopædia Britannica contains, of course, a complete encyclopædia of history within itself, and is the most modern of all such collections.[1] F. Ratzel’s History of Mankind, in spite of the promise of its title, is mainly a natural history of man, though it is rich with suggestions upon the nature and development of civilization. That publication and Miss Ellen Churchill Semple’s Influence of Geographical Environment, based on Ratzel’s work, are quoted in this Outline, and have had considerable influence upon its plan. F. Ratzel would indeed have been the ideal author for such a book as our present one. Unfortunately neither he nor any other ideal author was available.[2]

The writer will offer no apology for making this experiment. His disqualifications are manifest. But such work needs to be done by as many people as possible, he was free to make his contribution, and he was greatly attracted by the task. He has read sedulously and made the utmost use of all the help he could obtain. There is not a chapter that has not been examined by some more competent person than himself and very carefully revised. He has particularly to thank his friends Sir E. Ray Lankester, Sir H. H. Johnston, Professor Gilbert Murray, and Mr. Ernest Barker for much counsel and direction and editorial help. Mr. Philip Guedalla has toiled most efficiently and kindly through all the proofs. Mr. A. Allison, Professor T. W. Arnold, Mr. Arnold Bennett, the Rev. A. H. Trevor Benson, Mr. Aodh de Blacam, Mr. Laurence Binyon, the Rev. G. W. Broomfield, Sir William Bull, Mr. L. Cranmer Byng, Mr. A. J. D. Campbell, Mr. A. Y. Campbell, Mr. L. Y. Chen, Mr. A. R. Cowan, Mr. O. G. S. Crawford, Dr. W. S. Culbertson, Mr. R. Langton Cole, Mr. B. G. Collins, Mr. J. J. L. Duyvendak, Mr. O. W. Ellis, Mr. G. S. Ferrier, Mr. David Freeman, Mr. S. N. Fu, Mr. G. B. Gloyne, Sir Richard Gregory, Mr. F. H. Hayward, Mr. Sydney Herbert, Dr. Fr. Krupicka, Mr. H. Lang Jones, Mr. C. H. B. Laughton, Mr. B. I. Macalpin, Mr. G. H. Mair, Mr. F. S. Marvin, Mr. J. S. Mayhew, Mr. B. Stafford Morse, Professor J. L. Myres, the Hon. W. Ormsby-Gore, Sir Sydney Olivier, Mr. R. I. Pocock, Mr. J. Pringle, Mr. W. H. R. Rivers, Sir Denison Ross, Dr. E. J. Russell, Dr. Charles Singer, Mr. A. St. George Sanford, Dr. C. O. Stallybrass, Mr. G. H. Walsh, Mr. G. P. Wells, Miss Rebecca West, and Mr. George Whale have all to be thanked for help, either by reading parts of the MS. or by pointing out errors in the published parts, making suggestions, answering questions, or giving advice. The amount of friendly and sympathetic assistance the writer has received, often from very busy people, has been a quite extraordinary experience. He has met with scarcely a single instance of irritation or impatience on the part of specialists whose domains he has invaded and traversed in what must have seemed to many of them an exasperatingly impudent and superficial way. Numerous other helpful correspondents have pointed out printer’s errors and minor slips in the serial publication which preceded this book edition, and they have added many useful items of information, and to those writers also the warmest thanks are due. But of course none of these generous helpers are to be held responsible for the judgments, tone, arrangement, or writing of this Outline. In the relative importance of the parts, in the moral and political implications of the story, the final decision has necessarily fallen to the writer. The problem of illustrations was a very difficult one for him, for he had had no previous experience in the production of an illustrated book. In Mr. J. F. Horrabin he has had the good fortune to find not only an illustrator but a collaborator. Mr. Horrabin has spared no pains to make this work informative and exact. His maps and drawings are a part of the text, the most vital and decorative part. Some of them, the hypothetical maps, for example, of the western world at the end of the last glacial age, during the “pluvial age” and 12,000 years ago, and the migration map of the Barbarian invaders of the Roman Empire, represent the reading and inquiry of many laborious days.

The index to this edition is the work of Mr. Strickland Gibson of Oxford. Several correspondents have asked for a pronouncing index and accordingly this has been provided.

The writer owes a word of thanks to that living index of printed books, Mr. J. F. Cox of the London Library. He would also like to acknowledge here the help he has received from Mrs. Wells. Without her labour in typing and re-typing the drafts of the various chapters as they have been revised and amended, in checking references, finding suitable quotations, hunting up illustrations, and keeping in order the whole mass of material for this history, and without her constant help and watchful criticism, its completion would have been impossible.

SCHEME OF CONTENTS

| BOOK I THE MAKING OF OUR WORLD | ||

|---|---|---|

| PAGE | ||

| Chapter I. The Earth in Space and Time | 3 | |

| Chapter II. The Record of the Rocks | ||

| § 1. | The first living things | 7 |

| § 2. | How old is the world? | 13 |

| Chapter III. Natural Selection and the Changes of Species | 16 | |

| Chapter IV. The Invasion of the Dry Land by Life | ||

| § 1. | Life and water | 23 |

| § 2. | The earliest animals | 25 |

| Chapter V. Changes in the World’s Climate | ||

| § 1. | Why life must change continually | 29 |

| § 2. | The sun a steadfast star | 34 |

| § 3. | Changes from within the earth | 35 |

| § 4. | Life may control change | 36 |

| Chapter VI. The Age of Reptiles | ||

| § 1. | The age of lowland life | 38 |

| § 2. | Flying dragons | 43 |

| § 3. | The first birds | 43 |

| § 4. | An age of hardship and death | 44 |

| § 5. | The first appearance of fur and feathers | 47 |

| Chapter VII. The Age of Mammals | ||

| § 1. | A new age of life | 51 |

| § 2. | Tradition comes into the world | 52 |

| § 3. | An age of brain growth | 56 |

| § 4. | The world grows hard again | 57 |

| § 5. | Chronology of the Ice Age | 59 |

| BOOK II THE MAKING OF MEN | ||

| Chapter VIII. The Ancestry of Man | ||

| § 1. | Man descended from a walking ape | 62 |

| § 2. | First traces of man-like creatures | 68 |

| § 3. | The Heidelberg sub-man | 69 |

| § 4. | The Piltdown sub-man | 70 |

| § 5. | The riddle of the Piltdown remains | 72 |

| Chapter IX. The Neanderthal Men, an Extinct Race. (The Early Palæolithic Age) | ||

| § 1. | The world 50,000 years ago | 75 |

| § 2. | The daily life of the first men | 79 |

| § 3. | The last Palæolithic men | 84 |

| Chapter X. The Later Postglacial Palæolithic Men, the First True Men. (Later Palæolithic Age) | ||

| § 1. | The coming of men like ourselves | 86 |

| § 2. | Subdivision of the Later Palæolithic | 95 |

| § 3. | The earliest true men were clever savages | 98 |

| § 4. | Hunters give place to herdsmen | 101 |

| § 5. | No sub-men in America | 102 |

| Chapter XI. Neolithic Man in Europe | ||

| § 1. | The age of cultivation begins | 104 |

| § 2. | Where did the Neolithic culture arise? | 108 |

| § 3. | Everyday Neolithic life | 109 |

| § 4. | How did sowing begin? | 116 |

| § 5. | Primitive trade | 118 |

| § 6. | The flooding of the Mediterranean Valley | 118 |

| Chapter XII. Early Thought | ||

| § 1. | Primitive philosophy | 122 |

| § 2. | The Old Man in religion | 125 |

| § 3. | Fear and hope in religion | 126 |

| § 4. | Stars and seasons | 127 |

| § 5. | Story-telling and myth-making | 129 |

| § 6. | Complex origins of religion | 130 |

| Chapter XIII. The Races of Mankind | ||

| § 1. | Is mankind still differentiating? | 136 |

| § 2. | The main races of mankind | 140 |

| § 3. | Was there an Alpine race? | 142 |

| § 4. | The Heliolithic culture of the Brunet peoples | 146 |

| § 5. | How existing races may be related to each other | 148 |

| Chapter XIV. The Languages of Mankind | ||

| § 1. | No one primitive language | 150 |

| § 2. | The Aryan languages | 151 |

| § 3. | The Semitic languages | 153 |

| § 4. | The Hamitic languages | 154 |

| § 5. | The Ural-Altaic languages | 156 |

| § 6. | The Chinese languages | 157 |

| § 7. | Other language groups | 157 |

| § 8. | Submerged and lost languages | 161 |

| § 9. | How languages may be related | 163 |

| BOOK III THE DAWN OF HISTORY | ||

| Chapter XV. The Aryan-speaking Peoples in Prehistoric Times | ||

| § 1. | The spreading of the Aryan-speakers | 167 |

| § 2. | Primitive Aryan life | 169 |

| § 3. | Early Aryan daily life | 176 |

| Chapter XVI. The First Civilizations | ||

| § 1. | Early cities and early nomads | 183 |

| § 2A. | The riddle of the Sumerians | 188 |

| § 2B. | The empire of Sargon the First | 191 |

| § 2C. | The empire of Hammurabi | 191 |

| § 2D. | The Assyrians and their empire | 192 |

| § 2E. | The Chaldean empire | 194 |

| § 3. | The early history of Egypt | 195 |

| § 4. | The early civilization of India | 201 |

| § 5. | The early history of China | 201 |

| § 6. | While the civilizations were growing | 206 |

| Chapter XVII. Sea Peoples and Trading Peoples | ||

| § 1. | The earliest ships and sailors | 209 |

| § 2. | The Ægean cities before history | 213 |

| § 3. | The first voyages of exploration | 217 |

| § 4. | Early traders | 218 |

| § 5. | Early travellers | 220 |

| Chapter XVIII. Writing | ||

| § 1. | Picture writing | 223 |

| § 2. | Syllable writing | 227 |

| § 3. | Alphabet writing | 228 |

| § 4. | The place of writing in human life | 229 |

| Chapter XIX. Gods and Stars, Priests and Kings | ||

| § 1. | Nomadic and settled religion | 232 |

| § 2. | The priest comes into history | 234 |

| § 3. | Priests and the stars | 238 |

| § 4. | Priests and the dawn of learning | 240 |

| § 5. | King against priests | 241 |

| § 6. | How Bel-Marduk struggled against the kings | 245 |

| § 7. | The god-kings of Egypt | 248 |

| § 8. | Shi Hwang-ti destroys the books | 252 |

| Chapter XX. Serfs, Slaves, Social Classes, and Free Individuals | ||

| § 1. | The common man in ancient times | 254 |

| § 2. | The earliest slaves | 256 |

| § 3. | The first “independent” persons | 259 |

| § 4. | Social classes three thousand years ago | 262 |

| § 5. | Classes hardening into castes | 266 |

| § 6. | Caste in India | 268 |

| § 7. | The system of the Mandarins | 270 |

| § 8. | A summary of five thousand years | 272 |

| BOOK IV JUDEA, GREECE, AND INDIA | ||

| Chapter XXI. The Hebrew Scriptures and the Prophets | ||

| § 1. | The place of the Israelites in history | 277 |

| § 2. | Saul, David, and Solomon | 286 |

| § 3. | The Jews a people of mixed origin | 292 |

| § 4. | The importance of the Hebrew prophets | 294 |

| Chapter XXII. The Greeks and the Persians | ||

| § 1. | The Hellenic peoples | 298 |

| § 2. | Distinctive features of the Hellenic civilization | 304 |

| § 3. | Monarchy, aristocracy, and democracy in Greece | 307 |

| § 4. | The kingdom of Lydia | 315 |

| § 5. | The rise of the Persians in the East | 316 |

| § 6. | The story of Crœsus | 320 |

| § 7. | Darius invades Russia | 326 |

| § 8. | The battle of Marathon | 332 |

| § 9. | Thermopylæ and Salamis | 334 |

| § 10. | Platæa and Mycale | 340 |

| Chapter XXIII. Greek Thought and Literature | ||

| § 1. | The Athens of Pericles | 343 |

| § 2. | Socrates | 350 |

| § 3. | What was the quality of the common Athenians? | 352 |

| § 4. | Greek tragedy and comedy | 354 |

| § 5. | Plato and the Academy | 355 |

| § 6. | Aristotle and the Lyceum | 357 |

| § 7. | Philosophy becomes unworldly | 359 |

| § 8. | The quality and limitations of Greek thought | 360 |

| Chapter XXIV. The Career of Alexander the Great | ||

| § 1. | Philip of Macedonia | 367 |

| § 2. | The murder of King Philip | 373 |

| § 3. | Alexander’s first conquests | 377 |

| § 4. | The wanderings of Alexander | 385 |

| § 5. | Was Alexander indeed great? | 389 |

| § 6. | The successors of Alexander | 395 |

| § 7. | Pergamum a refuge of culture | 396 |

| § 8. | Alexander as a portent of world unity | 397 |

| Chapter XXV. Science and Religion at Alexandria | ||

| § 1. | The science of Alexandria | 401 |

| § 2. | Philosophy of Alexandria | 410 |

| § 3. | Alexandria as a factory of religions | 410 |

| Chapter XXVI. The Rise and Spread of Buddhism | ||

| § 1. | The story of Gautama | 415 |

| § 2. | Teaching and legend in conflict | 421 |

| § 3. | The gospel of Gautama Buddha | 422 |

| § 4. | Buddhism and Asoka | 426 |

| § 5. | Two great Chinese teachers | 433 |

| § 6. | The corruptions of Buddhism | 438 |

| § 7. | The present range of Buddhism | 440 |

| BOOK V THE RISE AND COLLAPSE OF THE ROMAN EMPIRE | ||

| Chapter XXVII. The Two Western Republics | ||

| § 1. | The beginnings of the Latins | 445 |

| § 2. | A new sort of state | 454 |

| § 3. | The Carthaginian republic of rich men | 466 |

| § 4. | The First Punic War | 467 |

| § 5. | Cato the Elder and the spirit of Cato | 471 |

| § 6. | The Second Punic War | 475 |

| § 7. | The Third Punic War | 480 |

| § 8. | How the Punic War undermined Roman liberty | 485 |

| § 9. | Comparison of the Roman republic with a modern state | 486 |

| Chapter XXVIII. From Tiberius Gracchus To the God Emperor in Rome | ||

| § 1. | The science of thwarting the common man | 493 |

| § 2. | Finance in the Roman state | 496 |

| § 3. | The last years of republican politics | 499 |

| § 4. | The era of the adventurer generals | 505 |

| § 5. | Caius Julius Cæsar and his death | 509 |

| § 6. | The end of the republic | 513 |

| § 7. | Why the Roman republic failed | 516 |

| Chapter XXIX. The Cæsars between the Sea and the Great Plains of the Old World | ||

| § 1. | A short catalogue of emperors | 52 |

| § 2. | Roman civilization at its zenith | 529 |

| § 3. | Limitations of the Roman mind | 539 |

| § 4. | The stir of the great plains | 541 |

| § 5. | The Western (true Roman) Empire crumples up | 552 |

| § 6. | The Eastern (revived Hellenic) Empire | 560 |

| BOOK VI CHRISTIANITY AND ISLAM | ||

| Chapter XXX. The Beginnings, the Rise, and the Divisions of Christianity | ||

| § 1. | Judea at the Christian era | 569 |

| § 2. | The teachings of Jesus of Nazareth | 573 |

| § 3. | The universal religions | 582 |

| § 4. | The crucifixion of Jesus of Nazareth | 584 |

| § 5. | Doctrines added to the teachings of Jesus | 586 |

| § 6. | The struggles and persecutions of Christianity | 594 |

| § 7. | Constantine the Great | 598 |

| § 8. | The establishment of official Christianity | 601 |

| § 9. | The map of Europe, A.D. 500 | 605 |

| § 10. | The salvation of learning by Christianity | 609 |

| Chapter XXXI. Seven Centuries in Asia (CIRCA 50 B.C. TO A.D. 650) | ||

| § 1. | Justinian the Great | 614 |

| § 2. | The Sassanid Empire in Persia | 616 |

| § 3. | The decay of Syria under the Sassanids | 619 |

| § 4. | The first message from Islam | 623 |

| § 5. | Zoroaster and Mani | 624 |

| § 6. | Hunnish peoples in Central Asia and India | 627 |

| § 7. | The great age of China | 630 |

| § 8. | Intellectual fetters of China | 635 |

| § 9. | The travels of Yuan Chwang | 642 |

LIST OF MAPS AND ILLUSTRATIONS

| PAGE | |

| Life in the Early Palæozoic | 11 |

| Time-chart from Earliest Life to 40,000,000 Years Ago | 14 |

| Life in the Later Palæozoic Age | 19 |

| Australian Lung Fish | 26 |

| Some Reptiles of the Late Palæozoic Age | 27 |

| Astronomical Variations Affecting Climate | 33 |

| Some Mesozoic Reptiles | 40 |

| Later Mesozoic Reptiles | 42 |

| Pterodactyls and Archæopteryx | 45 |

| Hesperornis | 48 |

| Some Oligocene Mammals | 53 |

| Miocene Mammals | 58 |

| Time-diagram of the Glacial Ages | 60 |

| Early Pleistocene Animals, Contemporary with Earliest Man | 64 |

| The Sub-Man Pithecanthropus | 65 |

| The Riddle of the Piltdown Sub-Man | 71 |

| Map of Europe 50,000 Years Ago | 77 |

| Neanderthal Man | 78 |

| Early Stone Implements | 81 |

| Australia and the Western Pacific in the Glacial Age | 82 |

| Cro-magnon Man | 87 |

| Europe and Western Asia in the Later Palæolithic Age | 89 |

| Reindeer Age Articles | 90 |

| A Reindeer Age Masterpiece | 93 |

| Reindeer Age Engravings and Carvings | 94 |

| Diagram of the Estimated Duration of the True Human Periods | 97 |

| Neolithic Implements | 107 |

| Restoration of a Lake Dwelling | 111 |

| Pottery from Lake Dwellings | 112 |

| Hut Urns | 115 |

| A Menhir of the Neolithic Period | 128 |

| Bronze Age Implements | 132 |

| Diagram Showing the Duration of the Neolithic Period | 133 |

| Heads of Australoid Types | 139 |

| Bushwoman | 141 |

| Negro Types | 142 |

| Mongolian Types | 143 |

| Caucasian Types | 144 |

| Map of Europe, Asia, Africa 15,000 Years Ago | 145 |

| The Swastika | 147 |

| Relationship of Human Races (Diagrammatic Summary) | 149 |

| Possible Development of Languages | 155 |

| Racial Types (after Champollion) | 163 |

| Combat between Menelaus and Hector | 176 |

| Archaic Horses and Chariots | 178 |

| The Cradle of Western Civilization | 185 |

| Sumerian Warriors in Phalanx | 189 |

| Assyrian Warrior (temp. Sargon II) | 193 |

| Time-chart 6000 B.C. to A.D. | 196 |

| The Cradle of Chinese Civilization (Map) | 202 |

| Boats on Nile about 2500 B.C. | 211 |

| Egyptian Ship on Red Sea, 1250 B.C. | 212 |

| Ægean Civilization (Map) | 214 |

| A Votary of the Snake Goddess | 215 |

| American Indian Picture-Writing | 225 |

| Egyptian Gods—Set, Anubis, Typhon, Bes | 236 |

| Egyptian Gods—Thoth-lunus, Hathor, Chnemu | 239 |

| An Assyrian King and His Chief Minister | 243 |

| Pharaoh Chephren | 248 |

| Pharaoh Rameses III as Osiris (Sarcophagus relief) | 249 |

| Pharaoh Akhnaton | 251 |

| Egyptian Peasants (Pyramid Age) | 257 |

| Brawl among Egyptian Boatmen (Pyramid Age) | 260 |

| Egyptian Social Types (From Tombs) | 261 |

| The Land of the Hebrews | 280 |

| Aryan-speaking Peoples 1000-500 B.C. (Map) | 301 |

| Hellenic Races 1000-800 B.C. (Map) | 302 |

| Greek Sea Fight, 550 B.C. | 303 |

| Rowers in an Athenian Warship, 400 B.C. | 306 |

| Scythian Types | 319 |

| Median and Second Babylonian Empires (in Nebuchadnezzar’s Reign) | 321 |

| The Empire of Darius | 329 |

| Wars of the Greeks and Persians (Map) | 333 |

| Athenian Foot-soldier | 334 |

| Persian Body-guard (from Frieze at Susa) | 338 |

| The World According to Herodotus | 341 |

| Athene of the Parthenon | 348 |

| Philip of Macedon | 368 |

| Growth of Macedonia under Philip | 371 |

| Macedonian Warrior (bas-relief from Pella) | 373 |

| Campaigns of Alexander the Great | 381 |

| Alexander the Great | 389 |

| Break-up of Alexander’s Empire | 393 |

| Seleucus I | 395 |

| Later State of Alexander’s Empire | 398 |

| The World According to Eratosthenes, 200 B.C. | 405 |

| The Known World, about 250 B.C. | 406 |

| Isis and Horus | 413 |

| Serapis | 414 |

| The Rise of Buddhism | 419 |

| Hariti | 428 |

| Chinese Image of Kuan-yin | 429 |

| The Spread of Buddhism | 432 |

| Indian Gods—Vishnu, Brahma, Siva | 437 |

| Indian Gods—Krishna, Kali, Ganesa | 439 |

| The Western Mediterranean, 800-600 B.C. | 446 |

| Early Latium | 447 |

| Burning the Dead: Etruscan Ceremony | 449 |

| Statuette of a Gaul | 450 |

| Roman Power after the Samnite Wars | 451 |

| Samnite Warriors | 452 |

| Italy after 275 B.C. | 453 |

| Roman Coin Celebrating the Victory over Pyrrhus | 455 |

| Mercury | 457 |

| Carthaginian Coins | 468 |

| Roman As | 471 |

| Rome and its Alliances, 150 B.C. | 481 |

| Gladiators | 489 |

| Roman Power, 50 B.C. | 506 |

| Julius Cæsar | 512 |

| Roman Empire at Death of Augustus | 518 |

| Roman Empire in Time of Trajan | 524 |

| Asia and Europe: Life of the Period (Map) | 544 |

| Central Asia, 200-100 B.C. | 547 |

| Tracks of Migrating and Raiding Peoples, 1-700 A.D. | 555 |

| Eastern Roman Empire | 561 |

| Constantinople (Maps to show value of its position) | 563 |

| Galilee | 571 |

| Map of Europe, 500 A.D. | 608 |

| The Eastern Empire and the Sassanids | 620 |

| Asia Minor, Syria, and Mesopotamia | 622 |

| Ephthalite Coin | 629 |

| Chinese Empire, Tang Dynasty | 633 |

| Yuan Chwang’s Route from China to India | 643 |

BOOK I

THE MAKING OF OUR WORLD

THE OUTLINE OF HISTORY

I

THE EARTH IN SPACE AND TIME

THE earth on which we live is a spinning globe. Vast though it seems to us, it is a mere speck of matter in the greater vastness of space.

Space is, for the most part, emptiness. At great intervals there are in this emptiness flaring centres of heat and light, the “fixed stars.” They are all moving about in space, notwithstanding that they are called fixed stars, but for a long time men did not realize their motion. They are so vast and at such tremendous distances that their motion is not perceived. Only in the course of many thousands of years is it appreciable. These fixed stars are so far off that, for all their immensity, they seem to be, even when we look at them through the most powerful telescopes, mere points of light, brighter or less bright. A few, however, when we turn a telescope upon them, are seen to be whirls and clouds of shining vapour which we call nebulæ. They are so far off that a movement of millions of miles would be imperceptible.

One star, however, is so near to us that it is like a great ball of flame. This one is the sun. The sun is itself in its nature like a fixed star, but it differs from the other fixed stars in appearance because it is beyond comparison nearer than they are; and because it is nearer men have been able to learn something of its nature. Its mean distance from the earth is ninety-three million miles. It is a mass of flaming matter, having a diameter of 866,000 miles. Its bulk is a million and a quarter times the bulk of our earth.

//////////////////////////

ruldiaryref https://www.gutenberg.org/files/45368/45368-h/45368-h.htm

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)